Sondheim enthusiasts might know Mary Rodgers primarily as the married friend he consulted to learn about marriage so that he could write the musical “Company.” Knowledgeable fans of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musicals (or Rodgers and Hart’s) would certainly know her as the daughter of composer Richard Rodgers. It probably takes true aficionados to recognize her as the composer of “Once Upon The Mattress,” the Broadway musical that made Carol Burnett a star, or as the author of “Freaky Friday,” the novel about a mother-daughter switcheroo whose sequels and movie adaptations kept her busy for twenty years.

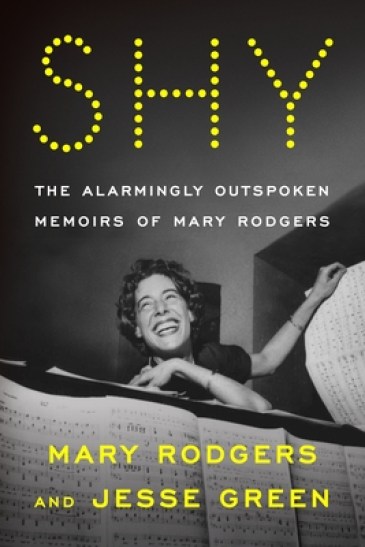

Each of these aspects of her life – and much more — is told in fascinating detail in Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 480 pages) written with New York Times chief theater critic Jesse Green, based on several years’ worth of twice-weekly interviews, and now published eight years after her death at the age of 83.

“Shy” is an entertaining read, and something more.

The person who emerges in this memoir is a smart, blunt, witty woman of surprisingly wide-ranging accomplishments – and, if not necessarily a central figure in the history of American musical theater, certainly a major witness to that history; she seems to have been a friend, lover, relative, employee, collaborator, acquaintance or enemy of most of the indisputably major musical theater artists of her day. These include Hal Prince and Stephen Sondheim, both of whom planned to marry her. (Her complicated, intense life-long involvement with Sondheim began when they met at Oscar Hammerstein’s house when she was 13 and he 14. He was the “love of my life…I just loved him, thoroughly enough for nothing else to matter. Do you not believe in that? Have you never seen Carousel?”) She was employed by Leonard Bernstein, helping to put together his Young People’s Concerts. She even helped create the next generation of musical theater artists, not just by serving for many years as the chair of the Board of Directors of the Juilliard School, but by giving birth to Adam Guettel, the Tony-winning composer of “The Light in the Piazza.”

There are plenty of anecdotes about the celebrated people she knew, which adhere to her dictum — uttered after Green delivered the first few pages of an early draft (as he explains in an afterword) — “Make it funnier. Make it meaner.”

By meaner, she really meant: more candid.

Mary Rodgers was of course a witness to musical theater genius from birth, none too willingly. She was not a fan of her father’s and mother’s parenting skills (her father told her when she was a young child “You are so fat you look like an ape”), nor their personalities, nor their largely fictitious memoirs (which in part is what motivated her to make hers as frank and true as possible.) On the other hand, “Daddy” and “Mummy” were always good with “the big things” (bailing her out when she got in trouble), and “I wasn’t embittered by him the way [her sister] Linda was. It was all about his music; everything loving about him came out in it, and there was no point looking anywhere else.”

She’s not any less clear-eyed about Daddy’s writing partner, whom she called Ockie. “Though Steve [Sondheim] would later describe Daddy as a man with ‘infinite talent but limited soul’ and Ockie as the opposite, the truth was more complicated.” Hammerstein was gifted and compassionate and a man of principle, but “I’d witnessed enough of Ockie’s behavior to know that he and Daddy, however different their demeanors, were absolutely alike in the way they indulged, prioritized, and protected their talent. Maybe you have to be at least a partial monster to clear the path to do great work.”

The title of the memoir is also the title of a funny and ironic song in “Once Upon A Mattress,” and her sly, clever description of this her first and most successful Broadway musical is telling:

“Once Upon A Mattress,” she says, is a “Borscht Belt retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairly tale ‘The Princess and the Pea,’ which tells the story of “a big, awkward, loudmouth princess, born to royalty but nevertheless a misfit…she has to outwit a vain and icy queen to get what she wants and live happily ever after.

“Story of my life, if only I’d realized it,” she adds, the start of a crucial paragraph:

“At the time, writing Mattress, I was in one of my periodic happily ever afters, which, spoiler alert, don’t last long. I was twenty-seven, freshly divorced, finally doing what I wanted the way I wanted, even if I was always terrified of failing. But one thing my life had shown me by then was that failing wasn’t so bad. In any case, it was inevitable, especially when your father was a god and your mother, well, a vain and icy queen.”

That line — “….failing wasn’t so bad…” – sums up much of what makes this book so worthwhile. “Shy” is full of stories of disappointment and outright heartache (an abusive first husband who was a closeted gay man; one of her six children dying when he was a toddler.) But it’s also a story of the grind — the everyday, practical challenges facing the average artist. Challenges such as getting a good agent. (“Agenting is less like marriage than foster care: You keep getting passed along.”) Such as getting attention to your show (She explains how she personally distributed show cards to every bar, restaurant and candy store in the theater district.) It’s rare for a memoirist to acknowledge outright failure, unless it’s a prelude to a spectacular comeback. It’s even rarer to dwell on false starts and unglamorous tasks, and admit to mediocre results.

Rodgers is more “outspoken” about her own failings than about anybody else’s. In pursuit of a career, she tells us, “my real thinking went deep underground while I took the course of least resistance. I behaved like my own worst enemies. I was, at least a little, an antifeminist woman, an anti-Semitic Jew, a snob bohemian.”

“Shy” contains Green’s extensive annotations at the bottom of almost every page, elaborating on names or incidents merely mentioned in the main narrative, sometimes gently correcting or disagreeing with what Rodgers has just said, often digressing into Green’s observations or opinions or occasionally some personal bon mots, the latter of which don’t always work. But the net result of his additions is to turn the book into something close to a solid work of theater history – which makes it all the more annoying that there is no index.

There’s something else “Shy” could use. There are hints throughout the book that Mary Rodgers had a deep talent for musical theater, and theater music — not just composition, but analysis. Perhaps because she wanted the book to be a fun read, we only get a few brief passages of analysis. But threaded through the book is also a tantalizing description of many of her songs — some of which delighted listeners in their day, and have largely disappeared in ours. Wouldn’t it be great to have a playlist of those songs – or even better, an album?