“The last great place to do Broadway musicals is in animation,” says Howard Ashman, in “Howard,” a new documentary on Disney+ that offers a simultaneously sad and inspiring look at Ashman’s life, his work, and his death from AIDS at the age of 40 in 1991.

What it doesn’t offer is a very encouraging take on Broadway.

This might come as a surprise for those theater lovers who committed to the monthly $6.99 Disney+ monthly subscription fee in order to see “Hamilton,” and expected “Howard” to be a follow-up effort to keep them subscribed.

After all, Ashman was a lyricist, librettist and director who collaborated with composer Alan Menken on “The Little Mermaid,” “Beauty and the Beast,” “Aladdin,” and ‘Little Shop of Horrors” — all of which have enjoyed a measure of success as musicals on Broadway — and, before that, with composer Marvin Hamlisch on the Broadway musical “Smile.”

But look closely: The first three musicals were originally created as Disney animated films, and were turned into stage musicals only after Ashman’s death; the fourth was produced only Off-Broadway (and made into a film) during his lifetime. The fifth, “Smile,” lasted only six weeks on Broadway. Although Ashman was nominated for a Tony Award for the book of “Smile,” the documentary makes clear that the musical’s lack of financial success made Ashman despondent, driving him out of Broadway and, soon, into the arms of Disney animation.

About halfway through the 90-minute documentary, at an event in 1988 at the 92nd Street Y, Ashman is asked: Is making a film out of a musical entirely different from making a film out of a play?

“Oh yeah. I think it’s an exercise in stupid,” he replies. “I don’t know why people think film musicals work…” They might have worked in the past, he says, but now “when people start to sing, it’s silly in the theater, and it’s even sillier when you’re taking a picture of it.”

He said that animation offered “a little corner of the world, where Broadway skills apply.”

A question prompted by that remark: Do Broadway skills apply elsewhere…like on Broadway?

The moderator asks him what he thought the future would be of the “American-initiated musical ” (this at a time when the most successful Broadway musicals were British exports.)

“I really don’t know. We’re all real depressed.”

The audience at the 92nd Street Y laughs. What they didn’t know, but the documentary tells us, is that very afternoon, Ashman’s doctor delivered his AIDS diagnosis.

Could this have colored his views? Perhaps. But at a moment three decades later when Broadway’s future is in doubt, and whatever theater we’re consuming is on screens, “Howard” recounts a life that feels relevant not just because it played out during an epidemic.

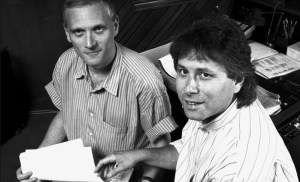

“Howard” is told in voiceover narration by people who knew him — no talking heads, as if filmmaker Don Hahn feared distracting us with the present. We learn from his sister Sarah Gillespie that Howard Ashman was a born theater maker. “Howard loved to tell stories, and my job as his kid sister was to be his best audience.” He would wear a bath towel as a turban, turn his toy soldiers, cowboys and Indians into characters from his imagination, painting them, dressing them with tissue, sprinkling them with glitter. As a boy, he created musicals in which he enlisted every child in the neighborhood, and as a teenager “musicalized everything,” including laundry lists, “as a hobby.” He met his first boyfriend, Stuart White, at a summer theater program, and they attended graduate school in theater together at Indiana University (initially as an actor), moved to New York, where a few years later they became co artistic directors of the Off-Off Broadway WPA Theater.

His first collaboration with Alan Menken was at the WPA, where he conceived, directed and wrote the lyrics for a musical adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s novel “God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater” It moved Off-Broadway, where critic Walter Kerr trashed it and it wound up “less successful commercially,” as Ashman puts it politely, in one of the many, many moments in the documentary in which he’s speaking directly to the camera (much of it likely to be interviews over the years promoting his latest project.)

All of this we learn in the first 20 minutes of “Howard,” and feels like the prelude to a story about a creative and tenacious life in the theater, especially since it’s followed by an absorbing account of his adaptation of the B picture “Little Shop of Horrors” into musical theater. Ashman saw the show as “the dark side of Grease,” and designed it to be both a conventional musical comedy and a parody of one. As he explains: Just like the female characters in My Fair Lady and Brigadoon sing about what she wants, so does Audrey, except she sits on a trashcan and what she wants is a toaster and a garbage compactor.

But the bulk of “Howard” is the story of Ashman’s work on the three hit animated Disney movies. A story told on Disney+ that focuses on Disney products can feel uncomfortably at times like self-promotion. But it is to Disney’s credit that “Howard” is also upfront about Ashman’s gay life, and about the horrors and the stigma of the epidemic that killed him. There is much in the documentary about his relationships, first with Stuart White, which ended because White was drinking too heavily and sleeping around, while Ashman wanted a spouse – which he found with architect Bill Lauch, who is one of the main narrators of the documentary.

If Ashman outwardly rejected Broadway — or, as he might have seen it, Broadway rejected him – it’s exciting to see the ways he transferred its lessons to a different medium. One animator on “The Little Mermaid” explains how Ashman told them that Ariel needed a “want” song. “We didn’t have a clue about that stuff.”

It’s thrilling to see Angela Lansbury and Jerry Orbach performing the soundtrack of “Beauty and the Beast” live in a studio with a full orchestra – “like a Broadway cast album,” as the film’s director Kirk Wise. It’s stunning to learn that the Oscar-winning songwriter wrote his last lyrics while in the hospital bed where he died.

For more about Howard Ashman,

check out HowardAshman.com